Chat V. Dang, MD (JJR65)

.

AT THE BEGINNING of the 3rd millenium, the moral fabric of East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam) remains Confucian in nature despite the powerful influence of Western and Marxist cultures. This is the result of centuries of education and culture based on the teachings of Confucius (551-479 BCE), after which East Asian societies were molded and their traditional leaders formed. Phan Thanh Giản (1796-1867) was an exemplary Confucian mandarin of the Nguyễn Court at a time it had to deal with the French conquest of Cochinchina then known as Nam Kỳ Lục Tỉnh (South Territory Six Provinces).

.

Family and Education

Phan Thanh Giản was born in 1796 in Bến Tre, southern Vietnam. His Chinese grandfather, faithful to the Ming, migrated from Fujian (Fukien, north of Guangdong) to Bình Định, central Vietnam, to escape the oppressive Manchurian Qing rule and married a Vietnamese woman. Born from this union, his father fled the instability of the Tây Sơn rebellion and moved to southern Vietnam. He worked there as a low-ranking administrative employee. When Giản was 6 (1802), his mother passed away and his father remarried. Giản was sent to study with the Buddhist monk Nguyễn Văn Noa at a pagoda.

In 1815, his father was falsely accused of corruption and incarcerated. The 19 year-old Giản, convinced of his innocence, wrote to the local administrator in Vĩnh Long to offer to take his father’s place in prison. Touched by the young man’s filial piety and intelligence, the official arranged for him to continue his study at a nearby facility so he could pay frequent visits to his father. After the latter had completed his sentence, the administrator convinced Giản to stay in town to further his study and take the competitive state examinations. In 1825, Giản passed the provincial exam in Gia Định to earn a bachelor degree (Cử nhân). The next year in the capital Huế, under the reign of Minh Mạng, he became at the age of 30 the first Vietnamese Southerner to earn a doctor degree (Tiến sĩ), ranking 3rd of 10 doctors of letters selected from 200 candidates.

.

High Mandarin of the Nguyễn Dynasty

Recognized for his outstanding Confucian formation, Phan Thanh Giản served as a mandarin under three Nguyễn monarchs, Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị, and Tự Đức. At the Huế court, he progressed rapidly through the ranks, becoming a high official in diverse ministries, a vice-ambassador to China, and a member of the royal Secret Council (Cơ Mật Viện). Strictly following Confucian principles, he incurred King Minh Mạng’s displeasure by honestly informing him of shortcomings in his edicts and practices. Once, he was downgraded to the rank of private. Remarkably, despite his upbringing as a man of letters, Giản bravely fought on the front lines against local rebels in Quảng Nam, central Vietnam. As a model of courage and discipline on the battlefield, he won the respect of his officers. On hearing this, Minh Mạng pardoned him and recalled him to court. Yet, his strict adherence to the ethical tenets of Confucianism resulted another time in his demotion to “Lục phẩm thuộc viên,” a public custodian sweeping Quảng Nam streets.

Under King Thiệu Trị (1841-47), Phan Thanh Giản was named Vice Chief Examiner of the national exams at the capital (Phó chủ khảo trường thi Thừa Thiên). Notably in 1856, under King Tự Đức (1847-83), he was in charge of the Court historians writing Khâm định Việt sử thông giám cương mục, a general history of Vietnam from the point of view of the Nguyễn dynasty. In 1851, he was sent to Nam Kỳ (South Territory) along with General Nguyễn Tri Phương to administer and defend the region under the threat of French colonialism.

.

The 1862 Treaty of Saigon

Despite the Treaty of Versailles signed in 1787 by Count Armand Marc de Montmorin(1*) and Pierre Pigneau de Béhaine, Bishop of Adran, representing Nguyễn Ánh, the pledge to militarily assist the future king Gia Long never officially materialized. Nguyễn Ánh ended reclaiming his throne thanks to his intelligence and tenacity, able military aides such as General Lê Văn Duyệt, the untimely death of his formidable enemy Emperor Nguyễn Huệ, and only a disparate small force of French volunteers and adventurers recruited by the Bishop of Adran.

In 1789, Nguyễn Ánh’s eldest son Prince Cảnh publicly refused to kowtow in front of the Nguyễn ancestors’ altar due to his newly adopted Christian beliefs. After the death of his trusted advisor the Bishop of Adran in 1799, King Gia Long distanced himself from new French missionaries and merchants. Indeed, heavily influenced by a court of Confucian-educated mandarins, King Gia Long and his successors felt more and more threatened by Catholicism to which 300,000 Vietnamese had quickly converted by the mid 1800s. Persecutions of Vietnamese Catholics under Kings Minh Mạng and Thiệu Trị were not met with decisive French reactions. In 1857, King Tự Đức executed two Spanish Catholic missionaries. This time, with French and English navies fighting the Second Opium War (1856-1860) in China, French forces were at hand to punish the Nguyễn Court. Then, East Asia weaponry was no match to advanced European military technology, a result of Napoleonic wars.

In 1858, following the failed diplomatic mission of Charles de Montigny, Franco-Spanish forces landed in Đà Nẵng and captured it. Unable to progress north, Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly directed his objective to Saigon and seized it in 1859. But soon, 15,000 Đại Nam [Vietnam] troops under General Nguyễn Tri Phương laid siege to Saigon. With the end of the Opium War, a French armada of 70 ships under Admiral Léonard Charner and 3,500 soldiers under General De Vassoigne were brought back to Saigon in 1861. The Franco-Spanish forces easily broke the siege of Saigon, then attacked the heavily defended Kỳ Hòa (Chí Hòa) fortifications. General Phương was hit in the forearm and his brother Duy killed by his side. Viet soldiers fought well with their outdated firearms, wounding De Vassoigne and Spanish colonel Palanca the first day. But they retreated when they thought their leader was killed when he was rushed away on a hammock. The camp fell after only 2 days of fighting. Fresh from their victory, the French took Mỹ Tho in April 1861. Replacing Charner, Admiral Louis-Adolphe Bonard took Biên Hòa and Vĩnh Long in early 1862.

French capture of Saigon in 1859. Courtesy of Wikipedia French capture of Saigon in 1859. Courtesy of Wikipedia |

The Huế Court was given a three-day ultimatum to sue for peace. Colonel Thomazi, the historian of the French conquest described : “On the third day, an old paddlewheel corvette, the Aigle des Mers [Hải Bằng], was seen slowly leaving the Tourane River. Her beflagged keel was in a state of delapidation that excited the laughter of our sailors. It was obvious that she had not gone to sea for many years. Her cannons were rusty, her crew in rags, and she was towed by forty oared junks and escorted by a crowd of light barges. She carried the plenipotentiaries of Tự Đức. [French corvette] Forbin took her under tow and brought her to Saigon, where the negotiations were briskly concluded. On June 5, a treaty was signed aboard the vessel Duperré, moored before Saigon.” Phan Thanh Giản as the main envoy (Chánh sứ), assisted by Lâm Duy Hiệp (Thiếp, Phó sứ), was charged to negotiate and sign the 1862 Treaty of Saigon (Hòa ước Nhâm Tuất). The treaty had 12 clauses, the most important being :

Art. 2- Đại Nam allows French and Spanish missionaries to preach and the Vietnamese to practice the Christian faith freely.

Art. 3- Đại Nam cedes to France the three eastern provinces of Biên Hòa, Gia Định and Định Tường and the island of Poulo Condor (Côn Đảo).

Art. 8- Đại Nam agrees to pay France 4 million dollars worth of silver(2*) over 10 years as war reparation.

Art. 11- France will return Vĩnh Long Province to Đại Nam once the three eastern provinces have been pacified.

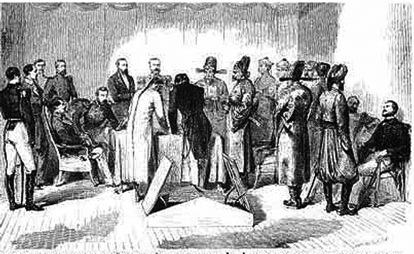

Phan Thanh Giản and Lâm Duy Hiệp presenting their credential letters to French Admiral Charner and Spanish Colonel Carlos Palanca Gutiérrez on the hospital ship Duperré in late May 1862. Phan Thanh Giản and Lâm Duy Hiệp presenting their credential letters to French Admiral Charner and Spanish Colonel Carlos Palanca Gutiérrez on the hospital ship Duperré in late May 1862. |

Because of his main role in the negotiations, Phan Thanh Giản was blamed by the Vietnamese people and the Huế Court. However, peace in the south allowed King Tự Đức to redirect his troops and put down rebellions in the north of Vietnam. In May 1863, in execution of the treaty, the Vĩnh Long citadel was handed over to Phan Thanh Giản, giving the Vietnamese and the royal court the hope to buy back the ceded territory. Indeed, the eastern provinces were Vietnam’s rice basket, the cradle of the Nguyễn restoration, the birthplace of Queen mother Từ Dũ, and the site of several Nguyễn ancestors’ tombs.

Embassy to France

.

Phan Thanh Giản was recalled to Huế to get instructions to conduct an extraordinary embassy to Paris and negotiate the return of the eastern provinces. The rumors in Saigon were that King Tự Đức was willing to pay 5 times more than the 4 million dollars agreed upon previously(3*). At the head of a 62-strong delegation which included Vice Ambassadors Phạm Phú Thứ and Nguyễn Khắc Đản (Đồng), and French-fluent scholar Petrus Ký, Phan Thanh Giản embarked on the transport vessel L’Européen on July 4, 1863, bringing with him lavish gifts for Napoleon III (a gold dragon-horse (long mã), a gold phoenix, exquisite jade objects, a gold sword, a jade tray, a silver washbasin, a silver box with ivory dividers, a silver vase binded with gold)(4*).

Artistic interpretation of the mythical dragon-horse (long mã) Artistic interpretation of the mythical dragon-horse (long mã) |

The Vietnamese arrived in Toulon on September 10, 1863, solemnly greeted by 17 cannon salutes and French Navy ships hoisting yellow flags symbolizing Đại Nam royalty. They were then taken to Marseilles by boat and treated to a tour of the port-city. They next boarded a train to Paris. The trip allowed them to witness with admiration the beauty and affluence of France’s countryside with no trace of wilderness left. They arrived in Paris on September 13, expecting an early audience with Emperor Napoleon III. The later, preoccupied by the Franco- Mexican War (1862-67) which consumed significant financial resources, had in principle agreed with his Minister of Finance Achille Fould to trade the conquered Cochinchina provinces for a sizeable amount of money to shore up the French treasury. While his minister launched a campaign to sway public opinion, starting with the newspaper L’Indépendance Belge claiming that King Tự Đức offered 85 million dollars to buy back his lost provinces(5*), the indecisive Napoleon III safely went on vacation in Biarritz, cautious of the division of French public opinion regarding the colonization and exploitation of foreign lands.

Phan Thanh Giản and his party were shown the marvels of French civilization the next 4 weeks. Reportedly, at a state reception in their honor, there were bowls of water at the table for washing hands but before dinner started, a Vietnamese official drank it, obliging the French hosts to do the same(6*). Finally, the embassy was received at the Tuileries Palace by Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie on November 7. Phan Thanh Giản gave his carefully prepared address, the full effect of which was lost in translation. However, “Looking old and fragile in his mandarin garb, he joined his hands to his forehead and humbly kowtowed three times, unlike French envoys who had refused to prostrate themselves before their own emperor. Then he wept while pleading his case. The spectacle was so pathetic that Empress Eugénie was moved to tears.”(7*) _ Napoleon III replied in general terms stating that France protected the weak, was a benevolent country that extended without restrain the benefits of civilization to all nations, but would be tough toward those who interfered with her progress. Somehow his last sentence was poorly rendered in Vietnamese by French Navy Captain and diplomat Aubaret as phải có sợ ̶ must have fear [of France], which terribly disheartened the Đại Nam envoys. The next day, the delegation was told that the French response would be given to the Huế Court in a year, and that in the meantime, commercial relations between the two countries could be improved. This gave the Vietnamese some hope although the status of the eastern provinces was left unanswered.

From Paris, the Vietnamese mission went to Spain. In December, it boarded a small Spain warship, the Terceira, to sail to Alexandria. En route, there was a violent storm and the Terceira had to drop anchor at Naples, Italy, for repairs. The two-week delay resulted in the terrible false news reaching Saigon that Phan Thanh Giản’s party was lost at sea. On March 18, 1864, the Vietnamese mission returned to Saigon aboard the transport ship Le Japon.

When Phan Thanh Giản reported that Europe’s wealth and strength were “startling”(8*), citing examples of technological innovation such as bridges constructed with steel (then a precious Đại Nam item reserved for the making of swords and other arms), steam locomotives that moved great distances without horses, and the superiority of gas lights over oil lamps, some Huế officials ridiculed them as tales from afar, ironically confirming the French saying A beau mentir qui vient de loin − easy to lie, coming from afar. King Tự Đức downplayed Western material supremacy with admonitions of moral rectitude :

“If faithfulness and sincerity are expressed

Fierce tigers pass by,

Terrifying crocodiles swim away

Everyone listens to Nghĩa (Righteousness)“(9*)

In the meanwhile, a mid-way decision was made by Napoleon III : France would keep the cities of Saigon, Cholon, My Tho and Thủ Dầu Một with a 5- kilometer zone on each side of the river joining these towns and the sea. The rest of the land would be returned in exchange for monetary compensation. When the offer finally reached Huế, King Tự Đức added modifications to the proposal, effectively rejecting it.

In Paris, after intense discussions, French Minister of the Navy and the Colonies Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat opposed the return of Cochinchina to Vietnam, and with the threat of resignation of the whole cabinet, forced Napoleon III to order the cancellation of the proposed agreement in June 1864. His decision would not reach Saigon until January 1865. Thus the Saigon Treaty of 1862 remained in full effect.

Nam Kỳ Lục Tỉnh (South Territory Six Provinces, 1841-62). Courtesy of Wikipedia Nam Kỳ Lục Tỉnh (South Territory Six Provinces, 1841-62). Courtesy of Wikipedia |

.

Last Governor of Southern Vietnam

Despite Phan Thanh Giản’s declination and request to retire at his age of 70, King Tự Đức appointed him Governor of the 3 western provinces of the South Territory in 1866. In this position, he had to delicately navigate between Southern Vietnamese fighters(10*) resisting French occupation, and Admiral De la Grandière who was quietly preparing to invade the remaining provinces used as sanctuary by the insurgency. At the beginning of 1867, Napoleon III sent a personal aide, Navy Lieutenant Des Varannes to Cochinchina to assess the situation. Upon receiving Des Varannes’ report, he gave the order to conquer the remaining western provinces of Cochinchina.

.

Complete Loss of Cochinchina

The French troops, consisting of 1000 Europeans and 400 Vietnamese recruits, boarded transport junks in the evening of June 17, 1867, supported by a fleet of gunboats (canonnières). On June 20, under the cloak of a thick morning fog, the French ships anchored undetected in front of Vĩnh Long, their cannons aimed at its remparts. Colonial troops quickly landed and blocked the citadel, whose defenders were caught by total surprise when they discovered their precarious situation at 7:30 AM. An ultimatum gave them until 2 PM to surrender.

Knowing that resistance was futile and would only lead to death and destruction, Phan Thanh Giản and his military commander Võ Doãn Thanh met De la Grandière. To buy time, they claimed that they had to get permission from the Huế Court. When the two Vietnamese leaders returned, Vĩnh Long had already surrendered and opened its doors to the French. In exchange for French authorities keeping southern Vietnamese officials and soldiers at their current posts and allowing those who wanted to be “repatriated” north to keep their arms, Phan Thanh Giản agreed to write two sealed letters to the Governors of the remaining 2 provinces An Giang and Hà Tiên. In the letters, he asked them to peacefully hand over their citadels to protect the lives of the common people because “the order of uprising has not been given.” He also declared that “the [French] tricolor flag would never wave high above a citadel where Phan Thanh Giản was still alive.”

Soon, feeling that he had failed to protect the land entrusted to him and had betrayed his people, Phan Thanh Giản stopped taking in nutrition. Still strong after 17 days, in the presence of his weeping family and in full ceremonial mandarin regalia, he bowed 5 times facing the North, and took a large dose of opium. French Navy Doctor Le Coniat attempted to revive the old mandarin who passed away 2 days later, at the age of 71. It was August 4, 1867(11*). Admiral De la Grandière sent a condolence letter signed the next day to Phan Thanh Giản’s oldest son Hương to express his respect : “The official testimony of my esteem and my friendship that I sent you in this letter must be preserved in your family as evidence of the feelings that the French people will preserve for your venerated father and his family(12*).”

Furious at the loss of the remaining Western provinces, King Tự Đức revoked all the titles of Phan Thanh Giản and ordered his name chiseled out from the Stele of Doctors (bia tiến sĩ). It was not until 19 years later, in 1886, that King Đồng Khánh rehabilitated his name and ordered it to be inscribed again on the Stele of Doctors.

Phan Thanh Giản had three sons, Phan Hương, Phan Liêm (Tòng), and Phan Tôn. After his death, the last two led a short-lived armed rebellion in French- occupied Cochinchina. Sentenced to death in absentia by the French, they rejoined the Huế capital. Serving under Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương(13*), they were captured at the fall of Hanoi on November 20, 1873 by Navy Lieutenant Francis Garnier who, a month later, was killed outside of Hanoi citadel by the Chinese Black Flags (Cờ Đen). The French government disavowed Garnier’s actions and released the Phan brothers to the Huế Court in 1874. Some history books have the two captured and executed by the French in Cochinchina due to a confusion with another resitance fighter also named Phan Tòng who died in the same battle that the Phan brothers had participated in(14*).

Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương (1800-1873) Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương (1800-1873)(Ảnh tư liệu của gia tộc, do hậu duệ là Nguyễn Tri Việt cung cấp – 2010) |

.

Tragic Destiny of a Dignified Scholar

French colonialist and historian Alfred Schreiner wrote this rave comment in 1906 “The indomitable energy of Nguyễn Tri Phương, the noble spirit of Phan Thanh Giảng, their general knowledge, have made these men, after Gia Long, the two most impressive characters in the modern history of Annam(15*)“.

Yet, the tragic destiny of Phan Thanh Giản, the first and only traditional Confucian Doctor of letters of southern Vietnam, did not end with his demise (1867), vilification (1868) and rehabilitation (1886). A century later, even though Phan Thanh Giản was revered in many southern villages as a dignified scholar, within weeks of the communist take over of South Vietnam, starting from early May 1975, streets bearing his name were relabeled with those of communist revolutionaries or victories, some of them never heard by the Vietnamese people. Built before 1945, the “Phan Thanh Giản” high school in Cần Thơ was the largest and most prestigious school in the Mekong delta. It too received a new name, and sadly, witnessed the statue of the venerated patriot erected in the early 1970s in its main courtyard smashed to pieces by the new authorities.

Did Phan Thanh Giản sell out his country (bán nước) when he chose to save innumerable innocent lives and death for himself ? Despite his admired virtues as an accomplished scholar, principled public servant, and compassionate human being, when would his tragic, up-and-down destiny finally lead him to permanent peace and recognition ? The first steps in the right direction might have been taken at the August 16, 2003 conference in Saigon “21st century : a look back at the historic person Phan Thanh Giản ̶ Thế Kỷ XXI nhìn về nhân vật lịch sử Phan Thanh Giản(16*).”

.

January 23, 2012 (Tết Nhâm Thìn)

Chat V. Dang, MD

From : Vietnam History – Stories Retold for a New Generation

.

1* France Minister of Foreign Affairs under Louis XVI

2* “Le Royaume d’ Annam n’ ayant pas de dollars, le dollar sera représenté par une valeur de soixante et douze centième de taël.” ̶ more than 20 millions Francs according to Alfred Schreiner in Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, p. 245.1906.

3* Schreiner, Alfred in Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, p. 254.1906.

4* http://dactrung.net/phorum/tm.aspx ?m=144914&mpage=3 Accessed 1-24-2012

5* Schreiner, Alfred in Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, p. 261.1906.

6* Told to the author by his grandfather poet and journalist Đặng Văn Chiểu.

7* Chapuis, Oscar. The last emperors of Vietnam : from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Press. Wesport, Connecticut. p.50. 2000

8* Từ ngày đi sứ đến Tây Kinh

Thấy việc Âu Châu phải giựt mình

Kêu rú đồng ban mau thức dậy

Hết lời năn nỉ chẳng ai tin.

9* Jamieson, Neil. Understanding Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 47. 1993.

10* The most famous were Trương Công Định (1863) and his son Trương Quyền (1865), Phan Chỉnh (1865), Nguyễn Trung Trực (1868), Nguyễn Hữu Huân (Thủ Khoa Huân, 1875), Võ Duy Dương, tức Thiên Hộ Dương, Trần Văn Thành (1873), Trần Văn Tấn (1881), Nguyễn Ngọc Hớn (1893) and his son Nguyễn Ngọc Sang.

11* Alfred Schreiner, in Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, p. 288, erronously wrote “5 Juillet” (July 5) for the 5th day of the 7th month of lunar year Đinh Mão. The corresponding date is actually August 4, 1867.

12* “Le témoignage officiel de mon estime et de mon amitié que je vous addresse dans cette lettre, doit être conservé dans votre famille comme le gage des sentiments que les Français conserveront pour votre vénérable père et pour sa famille.”

13* Wounded during the attack on Hanoi, Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương refused treatment and subsequently died.

14* http://vi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phan_Li%C3%AAm accessed Jan 22, 2012 23

15* “L’indomptable énergie de Nguyễn Tri Phương, la grandeur d’ âme de Phan Thanh Giảng, leur savoir général, ont fait de ces hommes, après Gia Long, les deux plus imposants charactères de l’histoire moderne d’Annam.” Alfred Schreiner, in Abrégé de l’histoire d’Annam, p. 126. 1906

16* http://www.gio-o.com/PhanThanhTamPhanThanhGian.html accessed Jan 28, 2012

.