Ho van Hien, MD (BP65)

.

BEFORE the 19th century, despite its rich literary tradition, Vietnam had few authors who devoted themselves to topics of practical importance, and to matters directly related to their own people and their country. Literati or Confucian scholars were educated in the neo-Confucian mold established centuries before by the Song scholars such as Chu Hsi (Zhu Xi, 1130-1200). Generally, they were more concerned with legitimacy and rites than the actual Vietnamese -not Chinese- environment where they were living, and where their countrymen were often suffering under repressive monarchs or village-based local authorities.

.

Building early Vietnamese Science

In the 18th century, there were two Vietnamese scientists who published prolifically in their fields. One was the famous physician Lê Hữu Trác (better known under his pseudonym Hải Thượng Lãn Ông, “The Lazy Man of Hải Thượng”) who wanted to continue the tradition of “Southern medicine for Southern people” initiated by Zen master-physician Tuệ Tĩnh in the 14th century. “Lãn Ông” forsook Confucian studies to devote his life to medicine, became the private physician of the lord Trinh for a while, but preferred to stay away from the capital city, to treat the common people and to disseminate his knowledge through his many publications, including a 20 volume treatise of traditional medicine (Hải Thượng Y Tông Tâm Lĩnh). The other was a Confucian scholar, whose wide range of interest, research and writing qualifies him as the most remarkable Vietnamese savant of the early modern period. Most significantly, he completed Vietnam’s first encyclopedia in 1773, at about the same period when Diderot and D’Alembert published their famous Encyclopedie (1751-1772) in France.

Lê Quý Đôn Lê Quý Đôn |

A Legend of Precocity

Initially named Lê Danh Phương at birth in 1726, Lê Quý Đôn’s story is full of anecdotes about his precocious intelligence and his presence of mind, which, even more than his scholarly genius and achievements, make him a legend among the Vietnamese for generations.

His father was the minister of justice at the Lê court in Thăng Long (Hanoi), having earned a doctorate degree at the traditional exam for the selection of public officials. At a very early age, Lê Quý Đôn demonstrated his skills in reading Chinese characters, text memorization and in the juggling of words. Before 24 months, he was able to recognize the Chinese words for “hữu” (have) and “vô” (without). At 5, he had read the whole Book of History (Kinh Thư), one of the oldest Chinese narratives, circa 6th century BCE). At 10, he studied history, and was able to memorize 80-90 pages every day. At 11, he was able to understand the Book of Change (Kinh Dịch), mostly used for divination ; and at 14, he had completed the study of all the classic texts of Confucianism.

.

Child Playing with Words

The following is one of the most well-known stories about this child prodigy. As he was running around naked, something considered normal for a young child of that period and even now in the Vietnamese countryside, one of his father’s friends came to visit. Like the Sphinx who would not let anybody passing through without an answer to its riddle, Quý Đôn spread wide his legs and arms (similar to Leonardo da Vinci’s famous “Man” drawing) and said :

− Please tell me which character it is, and I will take you to my house.

The man, a well-known scholar, was so angry at such an easy riddle thrown at him :

̶ Behave yourself, little brat. The answer is obvious ! All you have learned by eave-dropping is the character ‘Đại’ (大, big), and you dare challenge other people already ?

− Sorry sir, you are wrong, retorted the child. It has an extra stroke in the middle, so the answer is the character ‘Thái’ (太, very).

“Rắn đầu biếng học”

(double entendre : ‘Headstrong and Lazy’ or ‘Lazy Snakehead’), his most famous poem, was made when he was only a few years old. It is often cited as a proof of his precocity ; each verse contains a double entendre, playing in the double meaning of the word Rắn which in Vietnamese means both “snake” and “hard, obstinate” (rắn đầu). While serving as an obstinate and lazy student’s self-recrimination, it uses homophones that also describe the characteristics of different types of serpents.

Rắn đầu biếng học

Chẳng phải liu điu vẫn giống nhà !

Rắn đầu biếng học quyết không tha.

Thẹn đèn hổ lửa đau lòng mẹ,

Nay thét, mai gầm rát cổ cha.

Ráo mép chỉ quen tuồng lếu láo,

Lằn lưng chẳng khỏi vết roi da.

Từ nay Trâu Lỗ xin siêng học,

Kẻo hổ mang danh tiếng thế gia !

(Words with double meanings are in italic)

Headstrong and lazy student (literal translation)

Though different, still from the same family,

I must be punished, so stubborn and lazy.

The lamp oil is wasted ; Mother is hurt,

Father yells and howls day after day, his throat burns.

Always lying and clowning, parched lips,

My back can’t escape stripes from the leather whip,

From now on, I promise to study harder,

Lest my noble family’s reputation suffer !

Lazy snake-head (translation with snake related meanings)

Not a water snake [1], but a snake still,

Lazy snake-head [2], punish it they will.

Coral snake [3] fearing the study light, mother is hurt,

Golden-banded snake [4], from yelling father’s throat burns.

Rat snake [5], enough lying and clowning !

Whip snake [6], beware of stripes from whipping.

Rat snake [7], study hard from now on,

Cobra [8] family’s reputation must stay on.

1. Rắn nước 草花蛇 (thảo hoa xà, checkered keelback, Asiatic water snake, common scaled water snake, fishing snake, rice paddy snake) Xenochrophis piscator (họ Rắn Nước Colubridae)

2. ?

3. Rắn lá khô đốm 珊瑚蛇 (san hô xà, small-spotted coral snake, oriental coral snake) Calliophis maculiceps (họ Rắn Hổ Elapidae)

4. Rắn cạp nong 金環蛇, 金腳帶 (kim hoàn xà, kim cước đái, banded krait, golden banded snake) Bungarus fasciatus (họ Rắn Hổ Elapidae)

5. Rắn ráo 灰鼠蛇 (khôi thử xà), 細紋南蛇 (tế văn nam xà) (Indo-Chinese rat snake) Ptyas korros (họ Rắn Nước Colubridae)

6. Rắn roi 綠瘦蛇 (lục sấu xà), 大藍鞭蛇 (đại lam tiên xà), 鶴蛇(hạc xà) (oriental whip snake, green vine snake) Ahaetulla prasina (họ Rắn Nước Colubridae)

7. Rắn hổ trâu 南蛇 (nam xà), 滑鼠蛇 (hoạt thử xà) (common rat snake) Ptyas mucosus (họ Rắn Nước Colubridae)

8. Rắn hổ mang 印度眼鏡蛇 (ấn độ nhãn kính xà) (cobra, Indian spectacled cobra) Naja naja (họ Rắn Hổ Elapidae)

(Snake identification :

http://viet.gutenberg.free.fr/huediepchi/zPlants/squamataSpp.html )

.

A Law Scholar and a Warrior

In 1743, at the age of age 17, he was the first laureate of the provincial exam of Son Nam (thi hương). Afterwards, due to name confusion with a peasant rebel, he changed his name to Lê Quý Đôn. He spent the next 9 years in teaching students at his home and in writing. It was reported that he wrote ‘one hundred book chapters’ during that period, but this is not documented.

In 1752, he was ranked again as first laureate at both the metropolitan (thi hội) and the imperial palace examinations (thi đình) and earned the ultimate academic honor of being “three time first laureate” (tam nguyên). In 1754, he was assigned to a position at the Royal Academy, in the national history department (Toan tu quốc sử quán). Having earned the trust of the Trinh Lord, who was the actual ruler under the Lê King, Lê Quý Đôn was given different responsibilities as royal inspector in the provinces and military officer fighting rebels. He was recognized as an impartial inspector, giving honest report about observed incompetence and corruption.

In 1762, he was promoted in the Academy and 2 years later was sent in a two- year mission to China. After his experience in China, Lê Quý Đôn submitted to the Trinh Lord a petition for reform of the legal framework, calling for a government based on the rule by law, combined with Confucian rule by virtue (đức trị), but with emphasis on the first.

“Each person, he wrote, is born with a different constitution ; there are honest people ; there are violent people ; there are people who only carry on peacefully their business, on the other side there are thugs and tramps. Additionally, providing to every one’s need proved to be an impossible task even for the Yao and Shun Emperors (Nghiêu Thuấn), how can we want everyone to live according to their own wishes ?… Therefore, an enlightened ruler must create a legal framework (pháp chế) to control tightly his country, while using Confucius principle that “virtue is the essence of the Way, rite is the essence of worship (đạo cốt ở đức, tế cốt ở lễ)…The people’s mind is undecided, emergencies are not predictable, therefore governing the country is a very difficult endeavor ; and there is only one means to control people’s opinion and suppress subversion, it is the rule by laws.”

His piece of advice was not well received by the Lord and Lê Quý Đôn was assigned to a lesser position in a province in the north of the country. However, in 1767, with rebellions rampant among the countryside, induced by a prolonged drought, the new Trịnh Lord, Trịnh Sâm, needed Lê Quý Đôn’s help and summoned him to the court. Also, Lê Quý Đôn became vice-dean, then dean of the National Academy (Quốc Tử Giám) and was given the responsibility of reforming the highest educational institution reserved for the nobility and the talented scholars, first created in 1076 in Hanoi.

In 1770, after successful pacification campaigns against rebellions in Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An, he petitioned the Trịnh Lord to create plantations run by the military in the Southern frontier regions, for the purpose of increased food supply to the army, settlement and agricultural production of military personnel and their families, and revitalization of under-populated villages. However, the project was deemed unrealizable.

Trusted by the Lord Trịnh Sâm for his diligence and honesty, he was promoted quickly through the ranks at the court. He made recommendations regarding the current pressing problems : the educational system where promotion could be bought, influence peddling bypassing control by the central court in local administrations, corruption in allocation of public land and in the corvee systems, and corruption at the court as well as provincial level. Lê Quý Đôn was well recognized for his integrity and relentlessness in the fight against corruption.

In 1774, after Lord Trịnh Sâm took Thuận Hoá (Huế area) from the Nguyễn Lord, Lê Quý Đôn took part in a four-member committee from the court which remained behind to administer the newly conquered territory. He was sent to Thuận Hoá again in 1776 to reorganize the army. It was during this period that he wrote “Phủ Biên Tạp Lục”. Except for a temporary set back caused by a scandal involving his son cheating during an exam, and a charge of corruption levelled against him by the manager of a copper mine, Lê Quý Đôn was a faithful minister of Lord Trịnh Sâm at court and during campaigns against local rebellions, until his death in 1784 (or 1783, according to alternate sources)(*336).

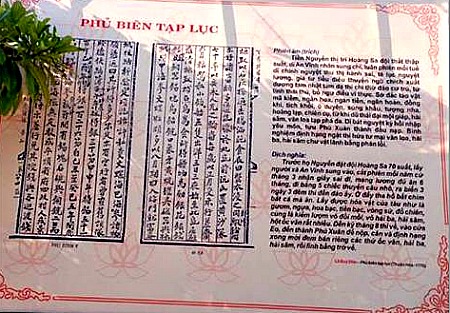

A page from Phủ Biên Tạp Lục describing the missions to Trường Sa and Hoàng Sa Islands by the Nguyễn Lords’ Navy. A page from Phủ Biên Tạp Lục describing the missions to Trường Sa and Hoàng Sa Islands by the Nguyễn Lords’ Navy. |

.

Literary Works

1) Đại Việt General History (Đại Việt Thông Sử, or Lê Triều Thông Sử [General History of the Lê Dynasty]). It was written in 1749, when Lê Quý Đôn was only 23 years old. According to Phan Huy Chú, author of Lịch Triều Hiến Chương Loại Chí, an encyclopedic work written from 1809 to 1819 under Emperor Gia Long, “The General History of the Lê dynasty has 30 volumes, and was prepared by Dr. Lê Quý Đôn. His book, very comprehensive and clear, may be considered to be the perfect history book of a dynasty.” The book provided new important information about Lê Lợi’s ten-year struggle against the Ming Chinese.

According to Cao Xuân Huy, only 3 volumes survived, with a foreword written by the author, and dated 1749(*337). Of great interest to students of Vietnam history is the following passage where Lê Quý Đôn deplored the paucity of documents that were available to him in the 18th century : “I have read book registries from the Han, Sui, Tang, Song eras, and found that they include more than a million books. These books and documents are catalogued in perfect order in royal libraries ; in scholars’ private residences, they are stored even more carefully. Their distribution is also very wide, so that, even after destructive wars, their loss is still negligible.

“We are a civilized country ; from our kings, our princes, down to their subjects, most of us can write. Nevertheless, all I can find is a little more than one hundred volumes ; compared to the number of Chinese works, this amounts to less than one tenth. Even with our few books, the way we keep them is really cursory : there are no designated storage facilities ; officials in charge of books do not have a formal office ; and there are no standards for book evaluation, copying, drying, storage ; no regulations at all. Even students chose only books useful to the successful passage of exams, for the purpose of getting a degree ; if they see a book that is not related to exam taking, they then skip it and would not deign to copy it ; even when they do copy it, it would be cursory work, without proper error checking. As for collectors of old books, they keep them in complete privacy, without letting anyone else knowing about their existence. Therefore, it is very difficult to find books, and when one finds them, they usually are filled with errors and gaps, and there is no way to correct them…” (*338)

2) Encyclopedia (1773)

His most remarkable work is an encyclopedic treatise named “Vân Đài Loại Ngữ”(*339). Vietnamese scholar Cao Xuân Huy considers it to be a kind of dictionary (loại thư) ;

“Vân đài loại ngữ is not a collective work like Chinese dictionaries, it is an individual work, and during its preparation, Lê Quý Đôn followed his own methodology.” _ The author took notes during his readings and catalogued them afterwards, adding comments about the subjects involved. His classification of subjects is much simpler than the Chinese one and involved 9 categories :

1) Lý khí : Universal principle and matter (sinitic Vietnamese for li 理 and qi 氣, generally speaking li is the principle, pure, is sheathed in qi, representing matter(*340), dealing with mostly cosmology according to neo-Confucian concepts

2) Hình tượng : Physical sciences, including astronomy ; geography ; calendars ; mentioning a discussion of alternate, “strange theories” (dị luận) e.g. theories about sea tides, the traditional 5 elements (Water, fire, wood, metal, earth) and their traditional correlation with the 12 signs of Chinese zodiac, etc … to derive moderate, reasonable conclusions.

3) Khu Vũ : Geography, administrative divisions in Chinese history

4) Vựng điễn : Traditional norms and customs.

The author was both conservative and tolerant of diverse customs :

“Governing of a country is “doing nothing” (vô vi). Legislation is essentially following previous generations. Human nature now is not very different from what it was in old times.

“The way we differentiate good and bad things is the same then and now.

The practice of ethics (lễ giáo) does not require changes in customs. Remedy to the social vices consists only in pointing out the truth.

“Being finicky about things long past and admiring modern things cannot be considered parts of the Way (đạo lý).”

5) Văn nghệ (Culture and society)

“Composing a report to the King, an introduction to a royal edict also relate to politics. Composing and reciting poetry are useless and are not considered literature (văn).”

“As to its source [of inspiration], everything should be oriented towards total integrity (thuần chính)”

6) Âm tự ; Language, letters. “Speech, writing and drawing styles are totally different in different countries, but ideas and what they mean (nghĩa lý) are the same.

Whatever is harmonious, balanced, simple should be used by people who need improvement.”

7) Thư tịch : Books. “The Five Classics (Book of Changes, Book of Poetry, Book of Rites, Spring and Autumn Annals), the Analects [of Confucius] and Mencius [collection of conversations with kings] are like the shining sun and moon…. If we can scrutinize them and summarize them, it will develop our intellect and benefit our spirit.”

8) Sỹ quy : Rules for literati “To venerate the King is to govern the people, to hold a mandarin position is to practice politics, the subject has to observe his loyalty, and the King has to teach his subjects strategies and tactics.”

9) Khí vật : Physics and natural sciences.

“The universe, without a conscience, transformed itself in ten thousand things that we use everyday without knowing it. Things we make are objects and tools that have names. As they grow, things in nature develop their shapes and their colors by themselves. Therefore, we should study their form and their classification from their beginning.”

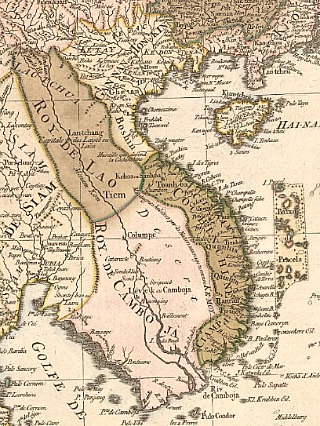

This 18th-century map of Vietnam derives from a map of southeast Asia and parts of China published in Amsterdam by the firm of Covens and Mortier around 1760. This 18th-century map of Vietnam derives from a map of southeast Asia and parts of China published in Amsterdam by the firm of Covens and Mortier around 1760. |

3) Phủ Biên Tạp Lục (1776) : ‘Frontier Chronicles’, in 6 volumes, was written when its author was sent to Thuận Hoá to reorganize the army.

1) How Thuận Hoá and Quảng nam were conquered from the Nguyễn Lord.

2) Their geography : mountains, rivers, roads, citadels

3) The organization of their government, taxation system, demographics.

4) Their taxation system and tax revenues.

5) Their human resources (e.g.“talented people”)

6) Natural resources, customs.

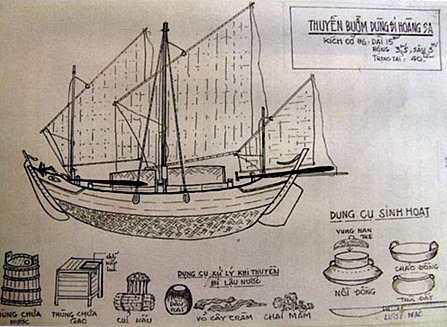

It is a detailed and systematic documentation of Central Vietnam in the 18th century. Recently, in the dispute between China and Vietnam about maritime boundaries, the Vietnamese side was fortunate to find in Phủ Biên Tạp Lục, an account written by Lê Quý Đôn in 1776, and mentioning the archipelagos of Hoàng Sa (Paracel Islands) and Trường Sa (Spratly Islands) off the Vietnamese coast as Vietnam’s territories. The document also relates how, once a year, the Lord Nguyễn sent out to these islands a special team on 5 small fishing boats which took 3 days and 3 nights to reach the islands. Their trips lasted about 6 months, and they lived on their abundance of fish and birds. They harvested carapaces of sea turtles, holothurians (sea cucumbers, hải sâm) and other precious sea products, and collected from ship wrecks horses, swords, watches silverwares, china, cooking oil. At their return in the 8th lunar calendar month, they had to go directly to Phú Xuân (Huế), the Nguyễn capital to hand in the trophies directly to the government. After which, they were allowed to sell the remaining of their sea product catch. This is a direct proof that these islands belonged to Đàng Trong (South Vietnam) under the Nguyen Lords(*341).

Technical drawing of the sailingboat and some other tools used for voyage to Hoang Sa – Photo : Summary records of Hoang Sa Technical drawing of the sailingboat and some other tools used for voyage to Hoang Sa – Photo : Summary records of Hoang Sa |

4) Collection of Vietnamese poems

In 1768, Lê Quý Đôn completed “Toàn Việt Thi Lục”, a collection of 6 volumes, containing 897 poems by 73 poets(*342), from 1009 (Lý dynasty) to 1516, and was rewarded with 20 silver teals.

Fame and Influence

Lê Quý Đôn is widely known and well respected in Vietnam. Streets, schools and even a university in Hanoi are named after him. Most lay people recognize his name because of widely taught tales about his precocity, his reported presence of mind, his quick repartees to adults as a child, or witty retorts to arrogant Chinese officials who challenged his learning. Nguyễn Gia Kiểng(*343), a critic of Vietnamese traditional thinking, wonders why Vietnamese do not keep literary giants like Lê Quý Đôn in their top honors list of heroes, and only reserve it to people who had achieved significant military feats, like Lê Lợi and Quang Trung (Nguyễn Huệ).

Part of the answer might be that, Lê Quý Đôn and famous scholars like him, despite their genius and brilliance, had only a limited effect of the course of the nation’s history and its destiny. The first reason is most of them followed the neo-Confucian mold, with almost absolute allegiance to their Kings or Lords. Although Lê Quý Đôn, like Korean emissaries to Beijing, had contact with western thinking through western books translated in Chinese, and though he made unsuccessful petitions for law reform to the Trinh Lord upon his return, his view and philosophy expressed in his books are mostly conservative neo-Confucianism. Second, as Lê Quý Đôn was well aware, at that point in the 18th century, Vietnam, although priding itself a country of culture, had a very limited book distribution network, and it’s doubtful that even allowed to be printed, they would have any significant impact on the general culture of that time.

Statue of Lê Quý Đôn in Saigon High School bearing his name ( formerly : Lycée Jean Jacques Rousseau). Statue of Lê Quý Đôn in Saigon High School bearing his name ( formerly : Lycée Jean Jacques Rousseau). |

Epilogue : old school learning and practical learning

As a reaction to the failure of traditional Chinese learning, silhak (Korean word for “practical learning,” thực học in sinitic Vietnamese) was developed in Japan in the 17th century by Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714) and in Korea by a persecuted catholic scholar, “Tasan” (Chong Yag-yong, 1762-1836) in the 18th century(*344). New knowledge about practical and society-oriented Western thinking were introduced by books from the West and translated into Chinese. Western ideas had been also imported to China by the Jesuits in the 17th and 18 centuries(*345). Vietnam had to wait another century to have a silhak catholic scholar named Nguyễn Trường Tộ who brought new ideas from Europe. However, even for Japan, it took another century for it to “orient itself” at the “civilized countries of the West“, leaving behind the “hopelessly backward” Asian neighbors, namely Korea and China”(*346), and enter the Meiji period (1868-1912). Korea really rose to progress only since 1963. As for Vietnam, sidetracked by a prolonged war and distracted by an ideological conflict, it is still lagging behind, under an authoritarian political regime, and still refusing to leave totally the neo-Confucian mindset of political indoctrination and rote learning.

.

November 20, 2011

Hien V. Ho, MD

From : Vietnam History – Stories Retold for a New Generation

.

*336. Trần Duy Phương, Lê Quý Đôn, Cuộc đời và giai thoại, Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Hoá Dân Tộc, Hà Nội, 2000. Trần Duy Phương wrote : “According to Phan Huy Chú and “Đăng Khoa lục bị khảo” Lê Quý Đôn died in the 44th Cảnh Hưng year [of the reign of King Lê Hiển Tông, who ascended the throne in 1740], at the age of 48 (year 1783). But according to other historical documents, Lê Quý Đôn died on the 14th day of the 4th month of the 45th Cảnh Hưng Year (1784) in the village of Nguyên Xá, district of Duy Tiên (now Phú Lý), which is the village of origin of Trương Lady, Lê Quý Đôn’s mother.”(p.38). Most biographical data and quotes in this article are from Trần Duy Phương’s book, two thirds of which are extensive reprints of translations of Lê Quý Đôn’s writings, published earlier in Vietnam.

*337. Trần Duy Phương, op. cit. p.50

*338. Quoted by Hoàng Trọng Miên, inViệt Nam Văn Học Toàn Thư, Xuân Thu Publishers (reprinted in the USA).

*339. Vân đài : a tower that ‘reaches the clouds’, bearing the names of famous ministers of the Han dynasty.

*340. Wikipedia : Neo-Confucianism.

*341. Nguyễn Quang Ngọc,” Người Việt đã xác lập và thực thi chủ quyền trên Hoàng Sa và Trường Sa,Viện Việt nam học và Khoa học và Phát triển (BienDong.Net).

*342. Trần Duy Phương, op. cit.

*343. Nguyễn Gia Kiểng, Whence…Whither…Vietnam ? (translated by Nguyễn Ngọc Phách), 2005

*344. Truong Ngoc Dung, Tuoi Tre

*345 http://www.ssu.ac.kr/web/museumeng/exhibit_a_04_01

*346 Yukichi Fukuzawa, quoted in Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meiji_period)

.